It would have been Ernest Hemingway’s 117th birthday this July. The anniversary did not go unmarked here in Hemingway’s hometown.

To skim the surface:

In July, the library’s Special Collections team participated in a conference of international Hemingway Society scholars who came to Oak Park. A gala was held at the Main Library to support the home, now a museum, where Hemingway was born. The library’s Executive Director, David J. Seleb, led a book discussion at the Oak Park Art League in conjunction with their Moveable Feast art exhibit. We compiled a volume of Hemingway-esque six-word stories written by local middle school students, and you can check it out at the library!

And before, during, and after it all, the library’s Special Collections team was working hard at Hacking Hemingway, the library’s grant-funded digital learning initiative that married old with new, paper with pixels, to create a digital collection for the world; and that expanded how local tweens and teens saw their hometown after interacting with artifacts of Hemingway’s time growing up in Oak Park.

“This summer, we had every part of the grant going,” said Leigh Tarullo, the library’s Curator of Special Collections. “It was well known at the Hemingway Society conference in July, and people were excited about it. We definitely took advantage of the local momentum to show off all the hard work we’ve been doing around the collection.”

A collection for the world

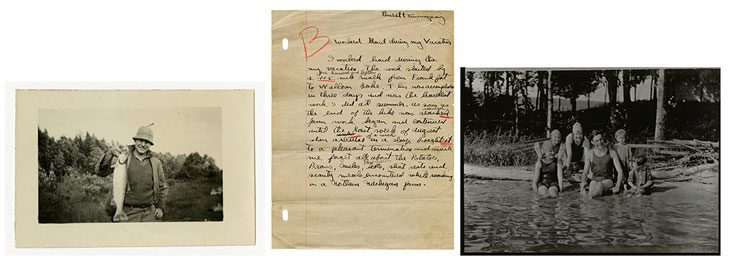

After more than a year of learning with the Hacking Hemingway grant, the library has completed its extensive online collection of nearly 350 photographs, letters, and essays from Ernest Hemingway’s early years in Oak Park.

Most of the artifacts, which are housed at the Main Library, are owned by The Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park; some are owned by the library. With the grant, the library turned the artifacts into digital images that are now available in the Illinois Digital Archives (IDA) collection “The Early Years—Ernest and Marcelline Hemingway in Oak Park.”

Resident Archivist Emily Reiher said that every day during the Hemingway Society conference, she was showing off the physical artifacts from the collection at the Main Library. “It was really exciting to have that face-to-face time with scholars,” Reiher said. “We were able to show these items in person to visitors from all over the world, who could then go home and revisit them online anytime.”

Who we’re hacking next

Through the Hacking Hemingway grant, Reiher said the foundation has been laid for new projects focusing on other parts of the library’s Special Collections.

“We want to keep the momentum going,” Reiher said. “We’ve collected a lot of great feedback from participants, and we want to build on what we’ve learned and continue to grow the connections we’ve made. We anticipate creating more programming that ties into our collection, and collaborating with new and current partners, especially Oak Park Elementary School District 97.”

So which famous, prolific Oak Park figure is next on the list?

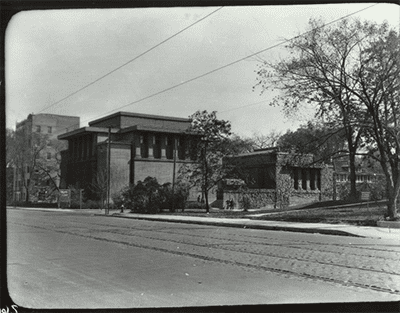

“The 150th anniversary of Frank Lloyd Wright’s birthday is next summer,” Tarullo said. “There’s going to be so much happening locally, as well as nationally and internationally, to celebrate Wright, whom many consider to be the 20th century’s greatest architect.”

Wright moved to Oak Park and constructed his home in 1889. Later he built an adjoining studio and developed his Prairie style there. The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, which operates his home and studio, notes that Oak Park’s Unity Temple, declared a National Historic Landmark in 1970, is Wright’s only surviving public building from his Prairie period.

The library’s Special Collections already has some archival material available online from its Frank Lloyd Wright collection, including photograph collections of his architecture. Other material available in the Main Library archives includes a first edition of Wright’s autobiography, plus binders of photographs, correspondence, clippings, and other materials related to his career and family.

Prairie-style pixels?

“Building on the success of the Hemingway MinecraftEdu program we did with Oak Park middle schoolers, we’re going to create a Frank Lloyd Wright MinecraftEdu program,” Reiher said. “We’ll take the participants’ comments and feedback, and launch it possibly in the spring with the same age group.”

For most of the kids who participated in Hemingway MinecraftEdu, Reiher said, it was their first time playing Minecraft in a physical location, in person with other players.

“They liked the guided experience and the ability to share as much as the actual act of building,” she said. “It offered a way for them to express their creativity, interact in the build site, and have time at the end to explain their creations to each other and have that audience of their peers. We’re hoping we can find a way to make the Frank Lloyd Wright experience even more collaborative.”