By Kristen Romanowski, Staff Writer & Editor

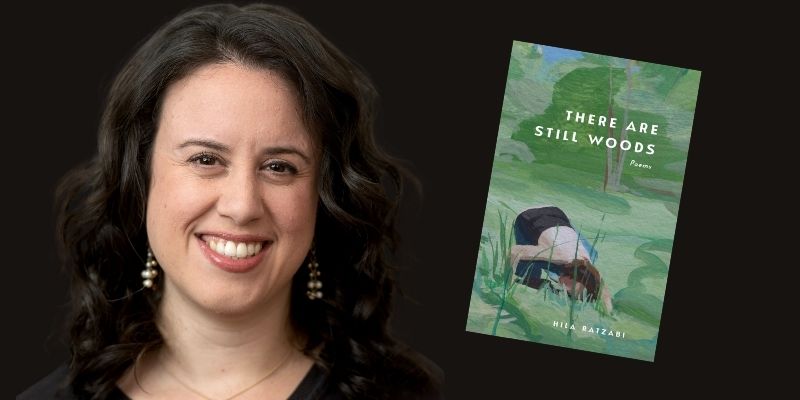

Hila Ratzabi became a poet at age 7. As a New York City kid growing up in Queens, she was composing poems about pigeons, steeping herself in Shel Silverstein, and falling in love with the music of language, the joy of playing with words.

“From that young age, it was just something that kind of came to me,” she says. “Both the artistic playfulness of it, but also this space to really question and find meaning in the world. It was always a little bit philosophical for me, to use poetry to think about a lot of big questions.”

In There Are Still Woods, Ratzabi’s first full-length book of poetry, she is exploring some of the biggest questions there are. The collection, which was published in September, bows down to the beauty and impermanence of the natural world and aches with its losses. Her poems brim with longing and awe, sorrow and love—all the terror and wonder that come from being an aware, sensitive human in a time of gun violence and climate change, space exploration and prestige television. One poem is titled “How to Pray While the World Burns.”

Join a poetry reading & climate conversation

On May 9 at the Main Library, Ratzabi will read from There Are Still Woods and lead a discussion and creative writing exercise on how we can respond to the climate crisis.

“I just really love hearing from people, and hearing where people are at and what’s been evoked in them from the poems,” Ratzabi says. “For many people, this is maybe even their first opportunity to just be thinking about these things and talking about these things in a more in-depth way than we really have spaces given to anywhere.”

Village of Oak Park Chief Sustainability Officer Marcella Bondie Keenan will also be there to talk about local efforts to respond to the climate crisis and how people can get involved.

“I love learning about this stuff,” Ratzabi says, “and I’m really hopeful that it will be an opportunity for people to feel like they can get involved in something that’s happening locally.”

Read on to hear more from Ratzabi as she speaks about her work, her influences, and her choice to not turn away from the climate crisis.

Writing ‘After Sandy’

Ratzabi started writing the poems in what became There Are Still Woods in 2012, the year Hurricane Sandy hit the Atlantic coast. She was living in Philadelphia at the time, and her parents were in Queens, where she grew up and where the hurricane caused substantial flooding and deaths.

She had first learned about global warming in eighth grade science class. And since seeing the film An Inconvenient Truth when it came out in 2006, she’d become increasingly aware of climate change—”but not super consciously, or it wasn’t something that I really wanted to focus on,” she says.

“But I think there was something about the experience of living through the hurricane, and then watching the aftermath, and just looking at all the pictures of the destruction, that just struck me as so powerful and so dramatic,” she says. “And maybe it was just closer to home because it happened in New York, and that’s where I’m from.”

In her poem “After Sandy,” Ratzabi takes the reader through images of the storm’s aftermath: “Piano on the sidewalk” in Queens. “Roller coaster dumped in the ocean” at the Jersey Shore. In Puerto Rico, “Man swept away by swollen river.”

Scientists later quantified how much worse the flooding damage was because of the rise in sea level caused by human activity. Of the estimated $60-$70 billion in damages, $8 billion could be attributed to human-caused climate change, researchers reported in 2021.

On not turning away

“As I started to experiment with writing different poems, I became much more consciously focused on climate change,” Ratzabi says. “And so it turns out that the poems became a form of witnessing that and a way of processing this information that I was taking in. But it was very much a conscious choice at some point to say, I’m going to look at this, and I’m not going to turn away from it.”

Still, she understands why people avoid the issue or don’t know what do to about it.

“I guess you have to protect yourself some,” she says. “And it’s also just, like, how do we process so many other catastrophes too, that are not just climate? There are so many other things that I don’t choose to pay attention to because I almost can’t handle them.”

“Because when you don’t experience the repercussions firsthand—which most of us are not, right now in the developed world, or in America—then it’s easy to just be like, oh, it’s happening to somebody else,” she adds.

“It’s just that we’re not on the front lines yet. Do we have to wait until it’s a full-on, in-your-face catastrophe, the hurricane is right at your door, before it becomes an emergency? It’s a very strange place to be in, because if you don’t feel the immediate sense of emergency at your doorstep then you’re not compelled to do anything. But it’s still happening, you know?”

The humanizing power of art

“There’s a lot of great art being produced right now that very much responds to climate change,” Ratzabi says. “It’s not solving any problems necessarily, but it’s bringing it into our collective consciousness. It’s making people look at it in maybe a different way.”

“Making some form of art can be transformative,” she adds. “There is something empowering about making something, whether it’s writing an essay, writing a poem, making a piece of art.”

And while art may not “fix” the problem, “it humanizes us as a society, as individuals, to care and to connect to these issues,” she says. “So I hope that in that way, it’s helpful and some kind of benefit.”

‘I don’t buy into any kind of fatalism’

“And at the same time, we have to do all the other things, right?” she says.

Signing petitions, composting, growing vegetables—Ratzabi does these, she says, “not thinking that any of them is going to make a huge difference in the long term, but that it changes me as a person, it changes my relationship to the earth. Hopefully, my kids are learning something from that too, so that they have a sensitivity to the lands that we’re on.”

And while individual actions are not enough on their own, while huge systemic changes are needed from governments and corporations—why not try anyway?

“It’s about what kind of a society do we want to be?” she says. “What are the values that we want to put out there? I don’t buy into any kind of fatalism or [think] it’s hopeless.”

“It’s also about changing how we live on a day-to-day basis, and how we interact with each other, and how our societies are structured, and how we share with our neighbors and connect with our local communities. Just building the kind of world that we want to live in.”

Influences, inspiration & where to find her

Read

After a childhood spent with Shel Silverstein and Jack Prelutsky, her favorite poets these days include Jorie Graham, Louise Glück, and Camille T. Dungy.

Plus: “The two poets who are always in the back of my mind are Li-Young Lee and Jane Hirshfield,” Ratzabi says. “I just feel like they’re kind of ancestor-type poets for me. They both find ways to engage with the world with a certain depth that I find really beautiful and inspiring, that I hope to get in my poems.”

For learning about climate change, ecology, and more, she recommends Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes From a Catastrophe and the authors Rebecca Solnit, Bill McKibben, and Joanna Macy.

Listen

Listen to the Spotify playlist she curated for There Are Still Woods.

Hear her read “Willapa Bay,” her favorite poem from the book, on the “Women in Wild Places” episode of the Citizens’ Climate Radio podcast.

Learn more

You can find a copy of There Are Still Woods in the library catalog, at The Book Table, and through June Road Press. Learn more about Ratzabi, including her upcoming workshops, at her website.